"Tradition is not something to be preserved. Tradition is something that has to be created." Kikuo Morimoto

IKTT Innovation of Khmer Traditional Textiles organisation

The IKTT specialises in the revival of Khmer silk ikat. Throughout history Khmer silk weaving has been regarded among the best in the world, however, after years of war, this ancient art form nearly vanished. The beauty of such silk has been its savior. Founded in 1996 by Kikuo Morimoto, we take a purist approach to the reproduction of traditional textiles, not just by recreating the style but by following the traditional practice seen a thousand years ago in the ancient times of the Angkor Dynasty. To achieve this, we have re-planted a traditional forest to cultivate everything from the natural dyes to the silk in a rich natural environment.

IKTT was renamed recently from Institute for Khmer Traditional Textiles

to: Innovation of Khmer Traditional Textiles organization

The Japanese Website:

The current collection and more information, on this website:

https://ikttcambodia.wixsite.com/iktt

IKTT on Youtube:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5xIhmKEhq_8As8b-YLIm0A

The two following domains are temporarily off:

For more Information visit the English website:

An older website with a wonderful diary from earlier years and more informations from that years 2003 to 2009 :

http://iktt.esprit-libre.org/en/

Full address IKTT town shop and office:

No. 456, Viheachen Village (Road to Tonle Sap Lake),

Svaydongkum Commune Siem Reap,

Siemreab-Otdar Meanchey, Cambodia

P.O. Box 93025

Opening hours: open daily from 8:00-12:00 /14:00-18:00

phone: +855 (0) 63-964-437 (english speaking)

How to find IKTT town shop in Siem Reap:

follow the Siem Reap River from the roundabout to the south on National Road 63 (also called Road to the Lake) and look to you right for a green sign with white letters saying IKTT, where the river makes a bend. Map IKTT

IKTT Weaving Village PWF (Project-) Wisdom from the Forest:

Opening hours: Monday to Saturday 07:00 - 11:00 / 13:00 - 16:00

Make an appointment at: iktt.info@gmail.com

Adress of PWF:

Chob Saom Village, Peak Snaeng, Angkor Thom District, Siem Reap

How to reach PWF Village:

The weaving village is located 30 km north of SR town.

Best way to get there is the road to Bantey Srey Temple site. Turn left at Wat Prey (IKTT sign) and follow the bumpy road for about 5 km. You will find the entrance to IKTT to your left side.

Copyright: NPO Textiles Across the Seas / photo by Hiroshi Kiuchi

"Institute for Khmer Tratitional Textiles" sowie dem Webedorf "Project Wisdom from the Forest" (PWF).

A report on the life and work of Kikuo Morimoto and IKTT.

Die Reportage ist auch online zu lesen:

auf www.weltwach.de:

Kikuo Morimoto und IKTT

Der Japaner Kikuo Morimoto kam vor über dreißig Jahren zum ersten Mal mit kambodschanischem Ikat in Berührung. Als freiwilliger Helfer in den Flüchtlingscamps der Khmer in Thailand erkannte er schnell die außerordentliche Schönheit der Webearbeiten und die Kunstfertigkeit der dort lebenden Flüchtlinge. Er war fasziniert von den detailreichen Mustern der Ikat-Stücke. Morimoto studierte die fast vergessenen, über 1200 Jahre alten Muster der Khmer. Er lernte die Techniken des Handspinnens und Handfärbens von kambodschanischer gelber Seide kennen, ebenso wie das Ikat-Reserveverfahren und die Ikat-Weberei. In Folge beauftragte ihn die UNESCO mit einer Recherche über den Zustand der traditionellen Seidenweberei in Kambodscha nach dem Krieg. Monatelang reiste er, teilweise unter Lebensgefahr, durch das zerrüttete und zerstörte Land und beschloss, hier zu bleiben und zu helfen. 1996 gründete er IKTT, wenige Jahre später legte er den Grundstein für das heutige Webedorf (das als Project Wisdom of the Forest bekannt ist) im Nordwesten Kambodschas.

Das Dorf ist angesiedelt auf 23 Hektar Land, in seiner Mitte stehen die Häuser der rund 30 Familien, rundherum wachsen Färbepflanzen, die in langjährigem Bemühen wiederaufgeforstet wurden und die immer wieder um neue Pflanzen erweitert werden – so etwa zuletzt um Indigopflanzen. Man findet Bananenbäume, deren Blattstängelfasern zum Abbinden der Ikat-Muster verwendet werden, Litschibäume, die die Seide grau färben. Maulbeerbäume wachsen dort, die das Futter für die immer hungrigen Seidenspinnerraupen liefern; fünf Brutzyklen gibt es im Jahr, vier davon werden zur Seidenproduktion genutzt. Unweit der Wohnhäuser befindet sich das Herz des Webedorfs, das Herz des ganzen Projekts: die Webe- und Färbewerkstätten. Zehn bis fünfzehn Webstühle sind laufend im Einsatz, im Nebenhaus wird gefärbt, im übernächsten werden Ikat-Muster abgebunden. Kinder laufen zwischen den Webstühlen, spielen oder schlafen in Hängematten. Eine Klingel ertönt: Der fahrende Händler ist da, es gibt Baguette mit Kondensmilch. Zwei Männer fällen einen Baum – Brennholz für die Färberei.

Das Dorf ist ein Ort der Schönheit, der Menschlichkeit und des Neuanfangs: Seit Jahren entstehen hier wunderschöne Textilien, alle von Hand gesponnen, gefärbt und gewebt: einfärbig oder in Fortführung der kambodschanischen Tradition mit klassischen Khmer-Mustern (wie der Naga, dem Baum des Lebens oder dem Diamanten) in den Farben Rot, Gold, Braun. Aber diese Tradition wird auch weitergeführt und bereichert: Junge, kreative Weberinnen entwerfen neue Muster, färben neue Farben wie Grau und Blau und tragen so die Tradition weiter.

Die schützende Hand, die beseelende Kraft ist Kikuo Morimoto. Er bezahlt seinen Weberinnen guten Lohn und kümmert sich darum, dass ihre Kinder zur Schule gehen können. Er beschäftigt auch die Männer der Weberinnen und hat für alle Sorgen der Bewohnerinnen und Bewohner ein offenes Ohr.

Bei Morimotos Reisen durch Kambodscha vor zwanzig Jahren hatte er Frauen gesucht und auch gefunden, die ihr Wissen und ihre Fertigkeiten über das Regime der Roten Khmer und den Bürgerkrieg hinaus bewahrt haben. In ganz Kambodscha hat er sie gefunden, in der Provinz Kampot im Süden, in der Provinz Takeo nahe Phnom Penh und auch im Norden des Landes. Sie, die Silk Grandmothers, wie er sie liebvoll nennt, sind es, die mit ihrer Erfahrung die Technik ebenso wie das Gefühl an die nächste Generation weitergeben. Ohne sie würde es all das hier nicht geben. From mother to daughter to granddaughter und nur aus dem Gedächtnis geben sie ihr Wissen weiter. Über 400 Weberinnen wurden seither von IKTT ausgebildet.

Klaus Rink & Barbara Giller, Wien, Nov. 2016

Brochure/Folder for IKTT, doublesided, 11" x 16" (US format)

Introduktion into IKTT and the work of Kikuo Morimoto;

in English and French language;

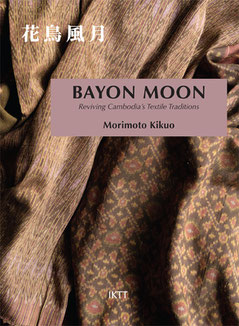

Bayon Moon by Kikuo Morimoto

E-Book, published September 2021

ISBN 978-3-200-07881-9

Pages: 168

at Apple Books:

https://books.apple.com/us/book/bayon-moon/id1587863443

Bookdescription:

In numerous essays, Bayon Moon tells the story of IKTT and the weaving village Project Wisdom from the Forest.

Morimoto Kikuo completed the manuscript for Bayon Moon during 2001–2002, as he was moving IKTT from Phnom Penh to Siem Reap and the workshop’s new

format was beginning to take shape. He started to accept salaried staff, whom he termed trainees, and a new kind of development was evident as their numbers increased and they were organized into

groups based on their responsibilities, including yarn processing, raw materials, dyeing, weaving, baskets, and events. In addition, that was the time when Morimoto was nurturing the “absolutely

impossible” possibility of “Project Wisdom from the Forest—a plan for revival,” and taking the first steps toward its actualization.

From Bayon Moon Epilogue, written by Jun Nishikawa

In Morimoto’s own words (2016): "This village is my (life´s) work. It is like drawing a picture. I dreamed up the landscape, the picture and it happened

for real."

Bayon Moon by Kikuo Morimoto

Printed Book, softcover, published September 2021

- ISBN-10 : 3200080825

- ISBN-13 : 978-3200080829

Kyoto Journal Issue 91 in memoriam- Morimoto Kikuo (1948 - 2017)

An article by Holly Thompson

in memoriam Morimoto Kikuo

the Kyoto-jin who built a village in Cambodia

We remember Kikuo Morimoto, who rebuilt war-torn Cambodia’s unparalleled heritage of silk weaving, in an interview with Holly Thompson;

you can order Kyoto Journal 91 here:

https://www.kyotojournal.org/product/kyoto-journal-issue-91/

During Corona times IKTT opened a new website which shows all their beautiful weaving products and will lead into an online-shop later on:

For the time beeing you can choose from the website and order via message to IKTT.

Write to

Saving Cambodia's Ancient Silk Legacy

National Geografic, December 2016

Japanese textile expert Kikuo Morimoto almost single-handedly revived the art of handwoven silks in wartorn Cambodia.

Article and Video about Kikuo Morimoto

The Rebirth of a Forgotten Cambodian Art

Kikuo Morimoto A village devoted to silk

Kikuo Morimoto has revived the ancient silk-making tradition from near-extinction in war-ravaged Cambodia, training new weavers and creating self-sustaining workshops.

Cultural knowledge and traditional skills were two of the lesser-known casualties of decades of conflict in Cambodia in the second half of the 20th century. During this period, a generation was deprived of the wisdom of the past, including the production of fine silk for which the country was famous.

read more:

https://www.rolex.org/rolex-awards/cultural-heritage/kikuo-morimoto

follow this link to the Rolex Award video:

https://www.rolex.org/rolex-awards/video/cultural-heritage/kikuo-morimoto

another version:

Silk Production and Marketing in Cambodia in 1995

A Research Report for the Revival of Traditional Silk Weaving Project, UNESCO Cambodia

About the Author and the Editor / Morimoto Kikuo (1948–2017) trained in

hand-painted silk textile decoration in Kyoto before moving to Thailand in 1973.

After completing his unesco-commissioned 1995 survey of textile production in Cambodia, he moved to that country to establish the Institute for Khmer Traditional Textiles (IKTT).

Louise Allison Cort is curator emerita for ceramics at the Freer Gallery of

Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Her research interests include ceramics, baskets, and textiles of Japan, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

Edited for and published at:

The Textile Museum Journal

Volume 46, 2019

A subscription to the whole journal is available through

the Textile Museum website.

Plesse find this link here:

https://museum.gwu.edu/tmjournal

One of the Best Silk of the World

Cambodia, Kikuo Morimoto, IKTT, Project Wisdom from the Forest.

Kambodscha - Die Seele der Seide

An ARTE Documentation from 2005.

From Carmen Butta

The early years of IKTT (in Siem Reap) and the beginning of +

"Project Wisdom from the Forest".

This Doc is only available as part of a DVD collection on

360° GEO Reportage.

"ASIEN - KONTINENT DER GEGENSÄTZE"

Available:

https://www.amazon.de/360%C2%B0-Reportage-Asien-Kontinent-Gegens%C3%A4tze/dp/B008IAQPE4

One of my favourite interviews with Mr. Kikuo Morimoto

Mr. Masaaki Kanai (President of Ryohin Keikaku Co.Ltd.) discussing with Kikuo Morimoto, 2013;

https://ryohin-keikaku.jp/eng/csr/interview/002.html

Mr. Masaaki Kanai (President of Ryohin Keikaku Co.Ltd.) discussing with Kikuo Morimoto, 2013;

this link moved to another place. find a pdf below:

Traces of War: The Revival of Weaving in Cambodia by Kikuo Morimoto (IKTT)

This report is the outcome of the research commissioned by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In this research, I visited more than 36 villages in 8 provinces between January and March 1995.

Because of the civil war disturbance beginning in 1970, few information relevant to textiles remained in Cambodia. Even maps, which are indispensable for a field survey, were not available at

first. My research, therefore, began with asking shopkeepers at the markets in Phnom

Penh, "Where did this fabric comes from?" Then, I arrived at remote villages, where I heard weaving activities still continues.

When I finished interview at such a village, I always asked the interviewees whether I could reach other weaving villages if I was to

proceed. I headed to other villages if they gave me directions.

Morimoto Kikuo "Resurrecting a Cultural Ecology"

An article by Molly Harbarger for Kyoto Journal KJ 73;

Author's Bio

Molly Harbarger is a senior at the University of Missouri studying journalism and international studies. She interned with Kyoto Journal while studying abroad in Japan. She has written for local newspapers The Columbia Missourian and Perry County Tribune.

an Interview with Kikuo Morimoto by Emily Taguchi (June 2007)

Interview With Kikuo Morimoto

by Emily Taguchi

Morimoto talks about reviving a tradition almost lost in the legacy of war and about his own drive for artistic perfection and social change.

Interview With Kikuo Morimoto, Director of the Institute for Khmer Traditional Textiles

Emily Taguchi: How did you become involved in Cambodian silk making?

Kikuo Morimoto: It started in 1980. When Cambodians began fleeing to refugee camps on the Thai border, I began volunteering at the weaving school at the camps. I used to work dyeing and hand painting kimonos in Kyoto. In 1994, I came to Cambodia for a UNESCO [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization] mission. During the 20 or so years following the 1970 civil war in Cambodia, no one knew who was weaving what fabrics in what villages. No one -- including the Cambodian culture ministry, arts colleges and nongovernmental organizations -- had any information about the tradition. So UNESCO commissioned me to do a study to find out whether or not this craft, which had been in Cambodia for thousands of years, still existed.

Bai Mai

A shop in Bangkok called Bai Mai.

[...] Mr. Morimoto was operating a small shop called Bai Mai (Leaf) on Ploenchit Road next to the old Erawan Hotel in the early 90 ties.

The shop sold the products of ethnic Khmer silk weavers living in villages in Surin province, Northeast Thailand.

The crisp, lustrous silk was dyed with natural dyes in pale pinks and creams and yellows, darker greys and browns. Most was sold as yardage, but some was tailored into cushion covers or blouses and shirts. In Bangkok—home of brilliantly colored, busily patterned “Thai silk”—it was a delightful surprise to find Thai silk with such subtle colors and robust texture.

Mr. Morimoto had come to Thailand as a volunteer to assist Lao weavers in refugee camps, leaving his work as a decorator of hand-painted yuzen kimono textiles in Kyoto.

After the camps closed, he stayed in Northeast Thailand

to pursue his interest in village traditions of natural dyes. This

led to the business he established as Bai Mai.

(Bayon Moon)

The Complex Art of Cambodian Ikat by Emily von Borstel

An article written August 2019 for the "Textile Arts Center" (New York)

https://textileartscenter.com/

Golden Silk, Cambodia by Emily Lush

An article written for

"The Textile Atlas"

About The textile Atlas (taken from the home page):

We tell stories through local and global voices, create connections in the field of Asian textiles.

The Textile Atlas is an accessible digital knowledge platform that presents traditional Asian textiles through local and global perspectives, highlighting artisan’s voices/practices and encouraging creative connections within the field of interest. Launched by Sharon Tsang-de Lyster of Narrative Made in 2017, The Textile Atlas takes on a holistic approach by incorporating field experience in both the private and public sectors, bridging the gap between local artisans, academia, and design businesses to enable new opportunities and articulate meaningful relationships based on unique cultural resources.

https://www.thetextileatlas.com/craft-stories/golden-silk-cambodia

find more from Emily Lush at her Travel Blog:

Restoring a Fine Khmer Craft Rent by Revolution by Rita Reif

An article from Rita Reif, written for the The Ney York Times, 1997

IN 1995, KIKUO MORIMOTO, a Japanese weaver and textile expert, traveled by motorcycle, by boat and on foot through the forests and jungles of Cambodia in search of master weavers. Everywhere he went, he showed pieces of boldly patterned Khmer silks taken from 19th-century costumes and temple hangings to shopkeepers in hopes of finding weavers who were still producing such work...

This article is behind a paywall

Technique of Natural Dyeing and Traditional Pattern of Silkproduction in Cambodia

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Phnom Penh office, 2007

English and Khmer Language

Please note:

this document is directly related to dyeing and weaving in Cambodia.

From the introduction:

UNESCO is much honored to have contributed to the successful publication

of this book about one of the most important traditional crafts in Cambodia;

natural dyeing. The completion of this publication bears testimony to the

continuous and intensive efforts of the Buddhist Institute to compile a very useful

document on the techniques of natural dyeing so that the future generations of

Cambodia may use these traditional techniques as a subsidiary occupation to improve their living conditions and to preserve their cultural heritage.